For Our Futures

Youth Voices on Climate Justice and Education

First Nations Justice

The Australian authors of this report acknowledge and pay our respects to Elders past and present. We recognise sovereignty was never ceded and that this land always was and always will be First Nations land. We recognise their ongoing connection to land, waters and community, and we commit to ongoing learning, deep and active listening, and taking action in solidarity.

We recognise that climate justice is dependent on First Nations justice. First Nations people in Australia are at the frontline of the climate crisis, and it is their knowledge of caring for Country for over 60,000 years that must be central to our climate responses. We are committed to our allyship and solidarity in the ongoing fight for First Nations justice and the long and continuing history of discrimination and disenfranchisement of First Nations people in Australia, most recently seen in the disappointing outcome of the Voice referendum.

As allies, we know that when it comes to First Nations justice and responding to the climate crisis, it is First Nations communities who have the solutions. It is critical that Australia listens and centres their knowledge in our climate response. Treaties are critical in this movement for change, recognising First Nations sovereignty, and custodianship of our land and waters.

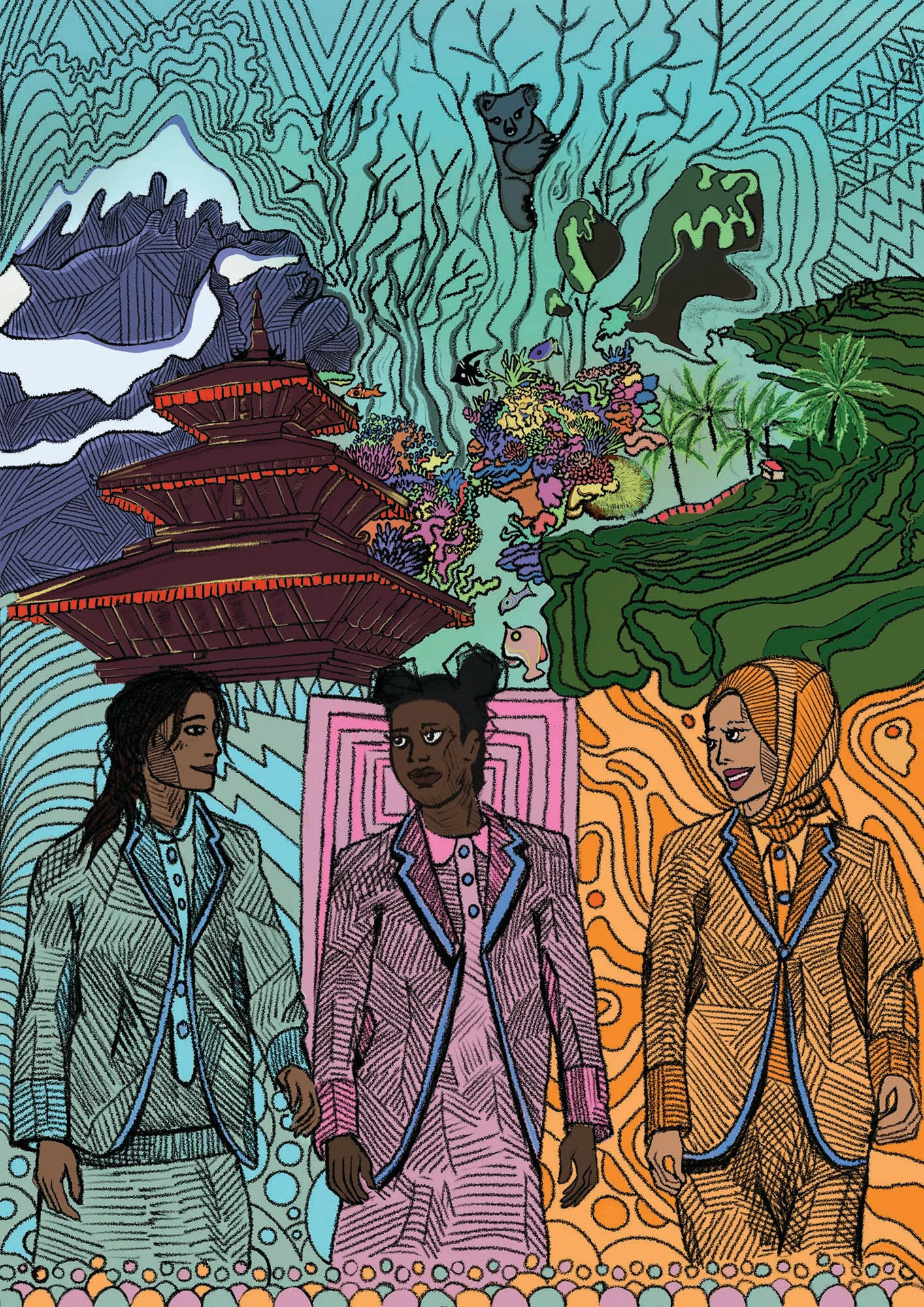

The team of young people leading this project

NEPAL

Babita, Bandana, Chetana, Manisha, Neha, Rehimat, Samikshya, Samita, Shikha and Sostika.

INDONESIA

Alif, Daffa, Dela, Devy, Dhita, Hilda, Rio, Roslin and Wigbertha.

AUSTRALIA

Allyza, Angelina, Chloe, Georgia, Iman, Lydia, Melis, Niranjana, Rabia and Rhiannon.

YOUTH ACTIVIST ALUMNI SUPPORTING THIS PROJECT

Bettina, Danielle, Grace, Imogen, Jazmin, Jemma, Kayshini, Naila and Olivia.

FOREWARD

As a youth activist from the heart of the Himalayas, Nepal, I am deeply honoured to introduce this collection of narratives and insights on the profound impact of climate change on girls' education in three countries: Australia, Nepal and Indonesia. The Youth Activist Series on Climate Change provided me with a platform to share my experiences and concerns, and I am humbled to be part of this vital dialogue.

Climate change exacerbates the challenges girls face in accessing education. Prolonged droughts, erratic monsoons, and extreme weather events disrupt their daily lives, making the journey to school perilous. Household responsibilities, intensified by climate-induced disasters, force many girls to drop out of school to support their families. These narratives shed light on their indomitable spirit as they strive to overcome these hurdles, proving that education is worth the sacrifice.

In solidarity – Chetana and Samikshya, Nepal

This new research undertaken by young people serves as one of the spaces for young people to address climate issues. Together with other young people from Australia and Nepal I discovered the diversity of climate change impacts affecting young people in each of our respective regions. Drought, pollution, waste problems, floods, the spread of diseases, and many other climate crisis issues have drawn our focus. Young people's great longing for change makes it both necessary and crucial. To bring about this transformation, we require unwavering support, space, and gratitude. Especially, in reality, development is slowed down for a variety of reasons, but the effects of climate change do not stop or wait for our reflection.

As an Eastern Indonesian woman, I also hope for that change. This project provides me with a platform to voice my aspirations as a young Indonesian concerning climate issues. I hope that this endeavour becomes a path towards a broader youth movement in addressing climate issues in each country. Just as change is necessary, we, as young people, have the right to make it a reality.

– Osin, Indonesia

We find ourselves at a critical juncture in the climate justice struggle. There is an urgent need for reform and action. Australia is situated in a part of the world where our neighbours are already experiencing life-changing and devastating effects due to climate change. However, we are still awaiting more definitive action from our government. This is a source of frustration for young people who are demanding swift action.

The title of our report "For Our Futures" encapsulates our key messages: our hopefulness, the steps we can take now to address the impact of climate change and save our futures, and the responsibility we, as the future generation, have in preserving the world we will inherit.

Our hope is that our message is heard and that our government takes responsibility. We are all in this together, and together, we are stronger.

– Rhiannon, Australia

KEY STATISTICS

In the next two years, it is predicted that more than 12.5 million girls may be prevented from completing their schooling each year, because of climate change.

of respondents said that they are very concerned or somewhat concerned about how climate change is affecting their school life, or how it will affect them in the future.

62% of respondents had experienced disruptions to their travel to and from school due to climate change.

Over 1 in 3 had seen their school closed, damaged or destroyed due to climate change related events.

‘Less power to make decisions about my future’

was what 69% of respondents, in Australia, said was one of the top concerns they had about how climate change was impacting their education.

At least 35,300 schools in Indonesia have been impacted by disasters from 2005 to 2019.

respondents felt unsafe at school or travelling to and from school due to climate related disasters.

of respondents wanted to learn more skills for green jobs in the future.

In Nepal, it is estimated that students are losing up to three months of education every year, due to climate disasters. During the 2017 floods, almost 2,000 schools were damaged or destroyed, and around 238,900 children missed school. In the worst hit areas, 90% of schools were destroyed.

In Australia, the 2019-2020 bushfires affected approximately 1.65 million people in NSW alone. 30% were children and young people aged 0-24 years. Almost one in ten children and young people impacted by the bushfires were First Nations young people.

respondents wanted girls to be taught more about how to prepare for disasters.

In Indonesia, over 50% of respondents were concerned about a decline in their academic performance due to climate events disrupting their education.

children in Indonesia, in 2021 had their education disrupted by flash floods and landslides.

In Australia, the 2022 floods in NSW and Queensland lead to the temporary closure of almost 1,000 schools.

METHODOLOGY

For Our Futures: Youth Voices on Climate Justice and Education engaged 30 young change makers across Australia, Indonesia and Nepal using a Feminist Participatory Action Approach to co-research the impact of climate change on girls’ right to an education. The approach included training and equipping young people with the skills to advocate for change. This took place over six online cross-country workshops and ongoing in-country engagement with youth activists.

502 young people completed the online survey.

- 154 from Indonesia

- 182 from Nepal

- 166 from Australia

96 photos, videos or graphic representations were received.

- 29 from Indonesia

- 55 from Nepal

- 12 from Australia

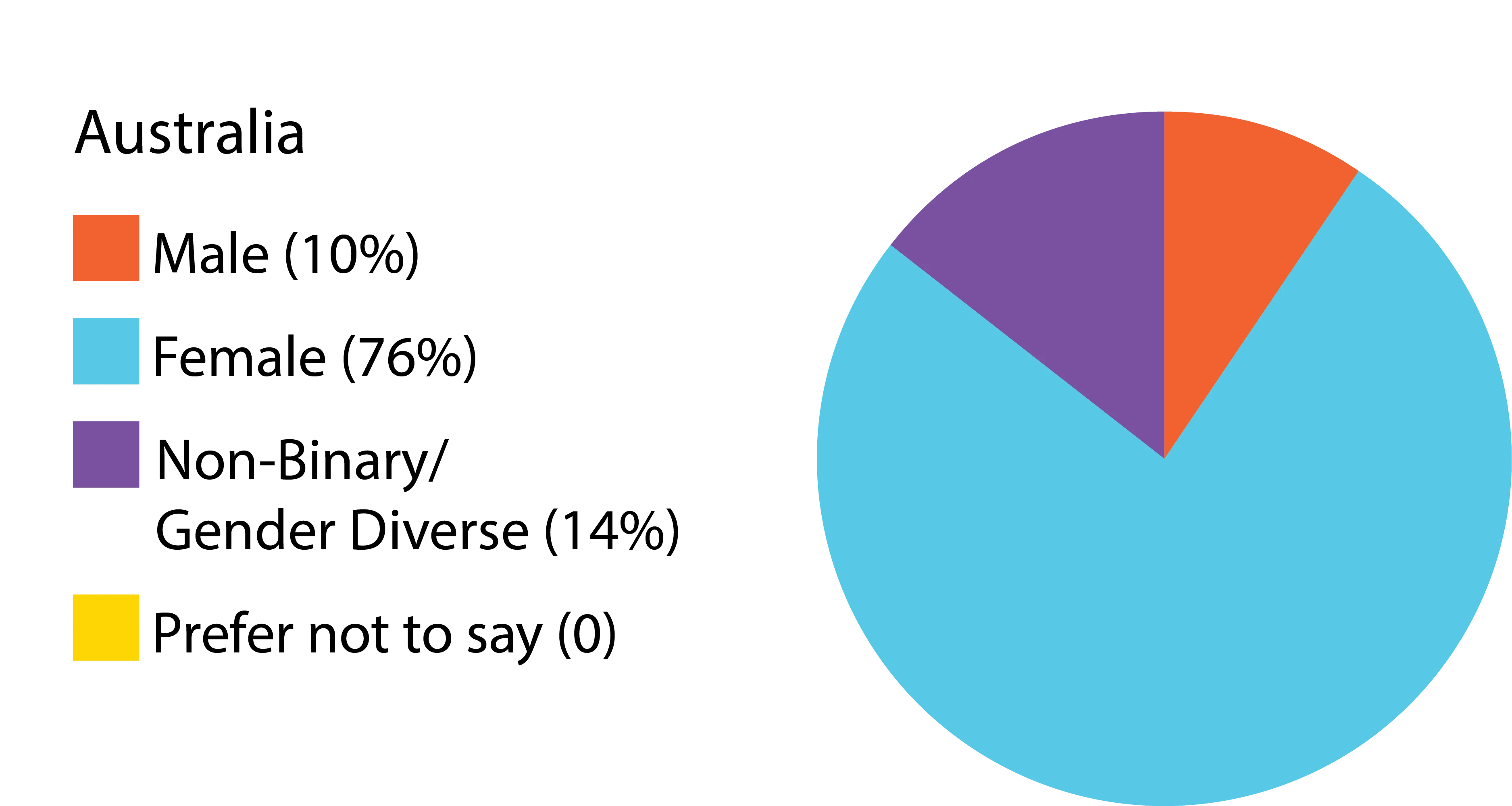

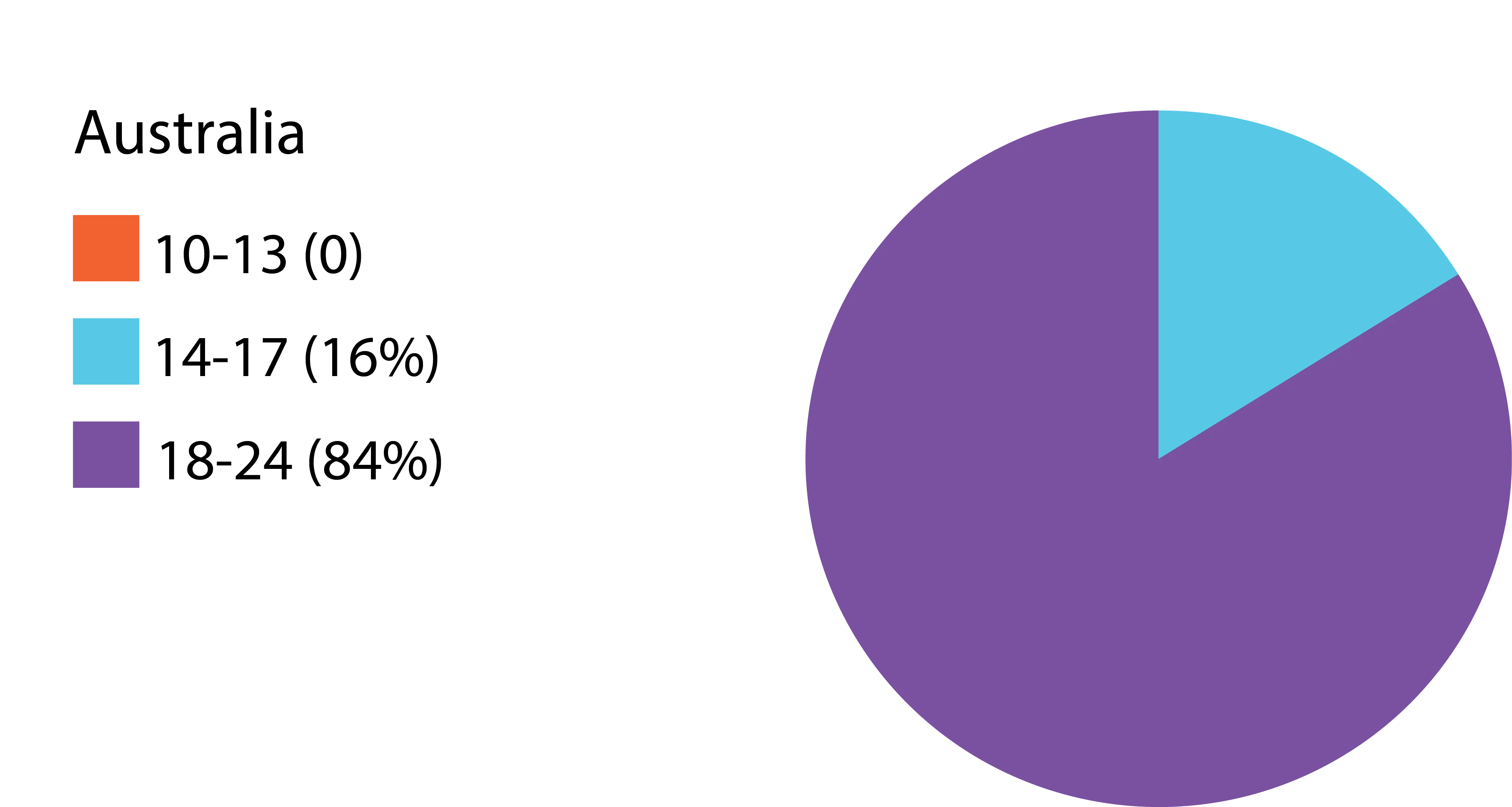

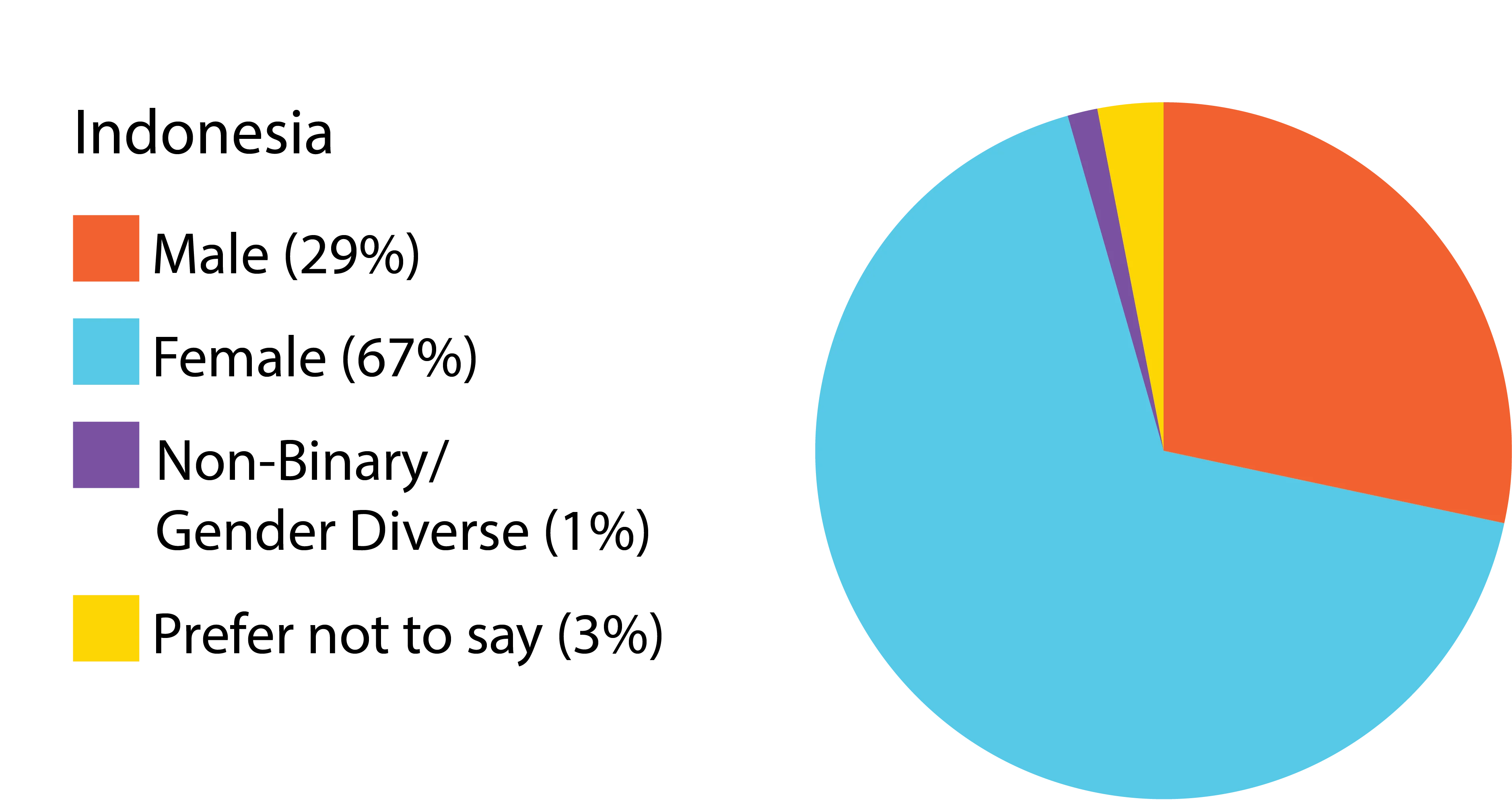

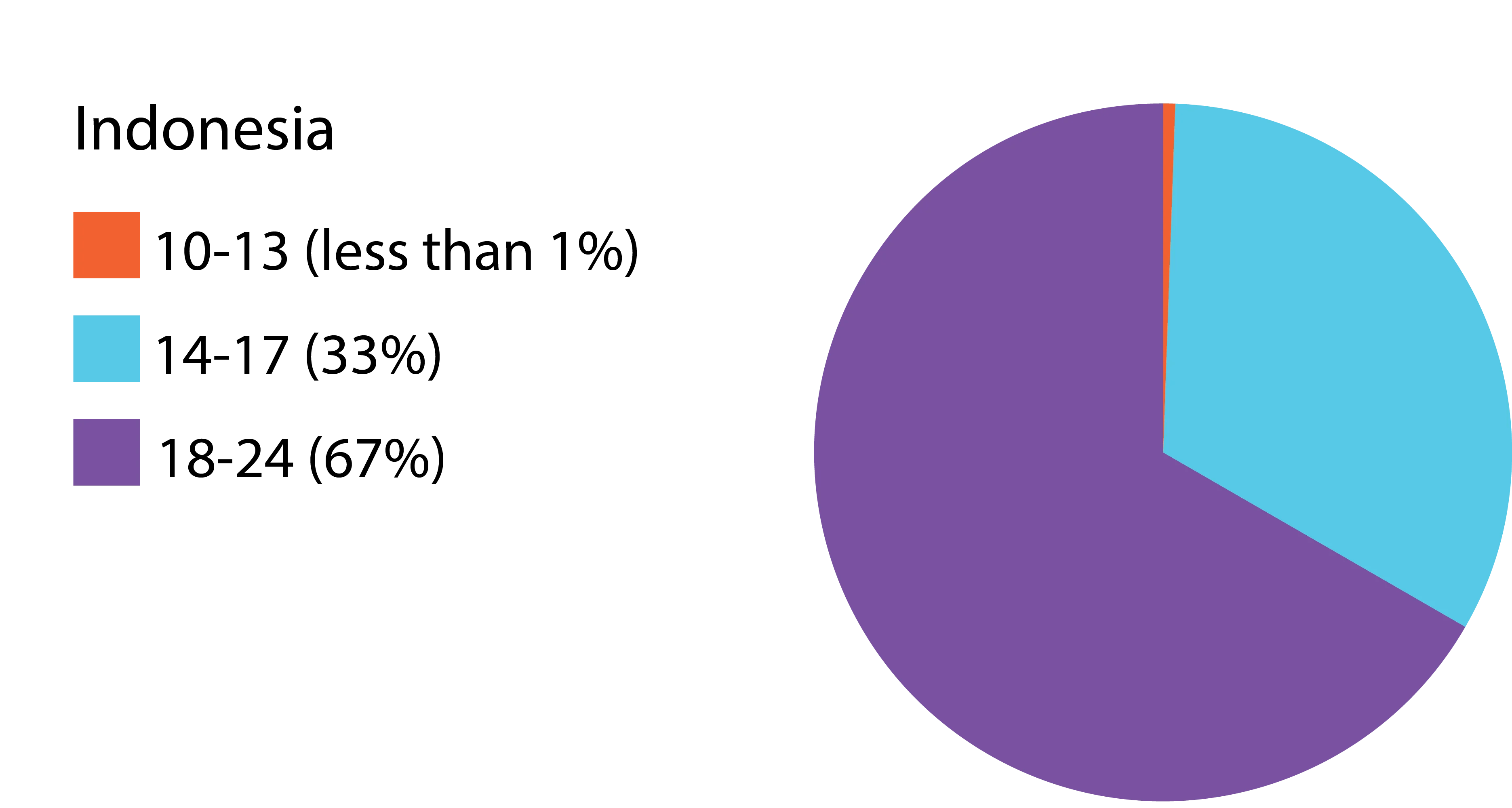

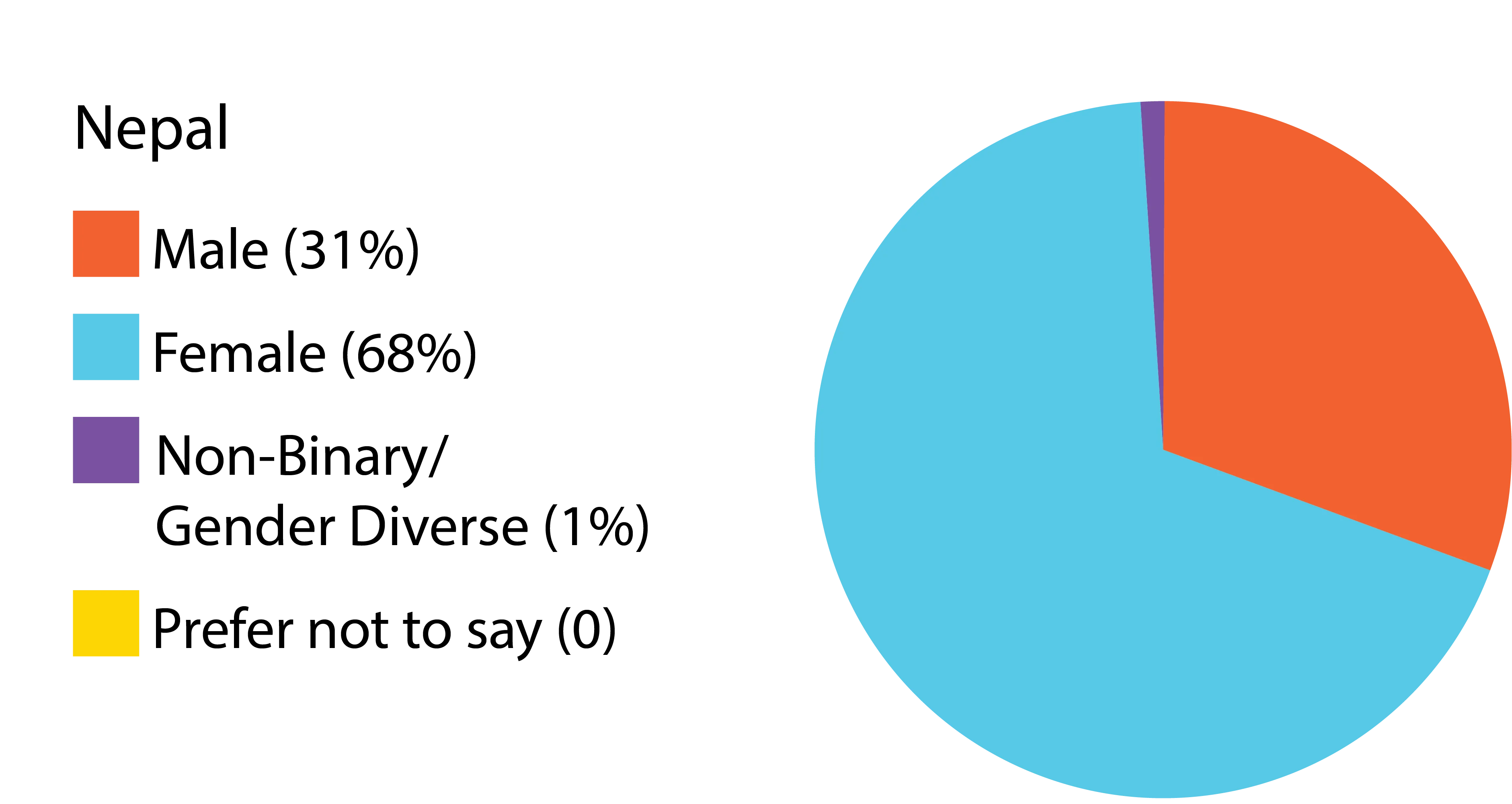

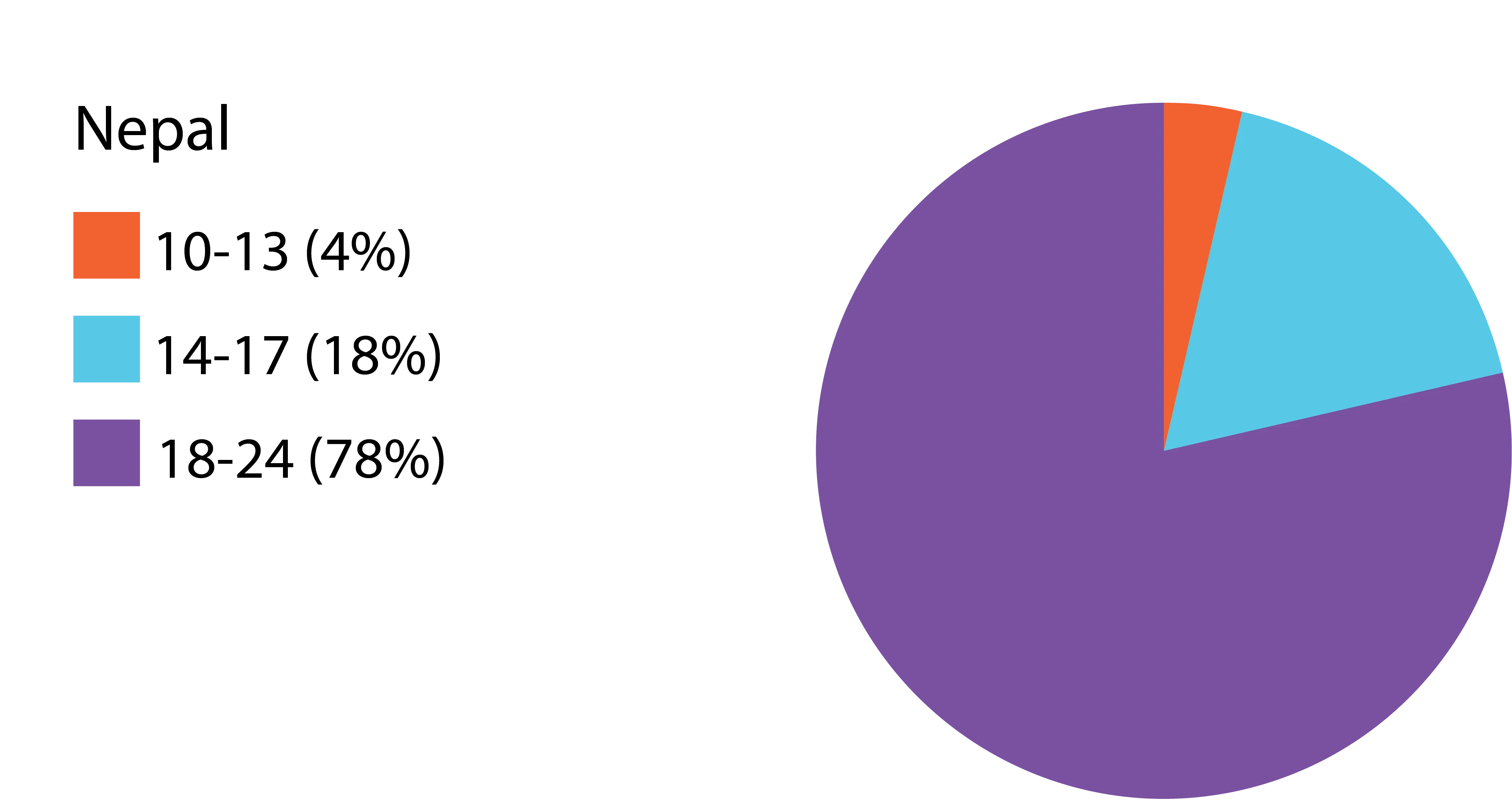

Breakdown of respondents by gender and age

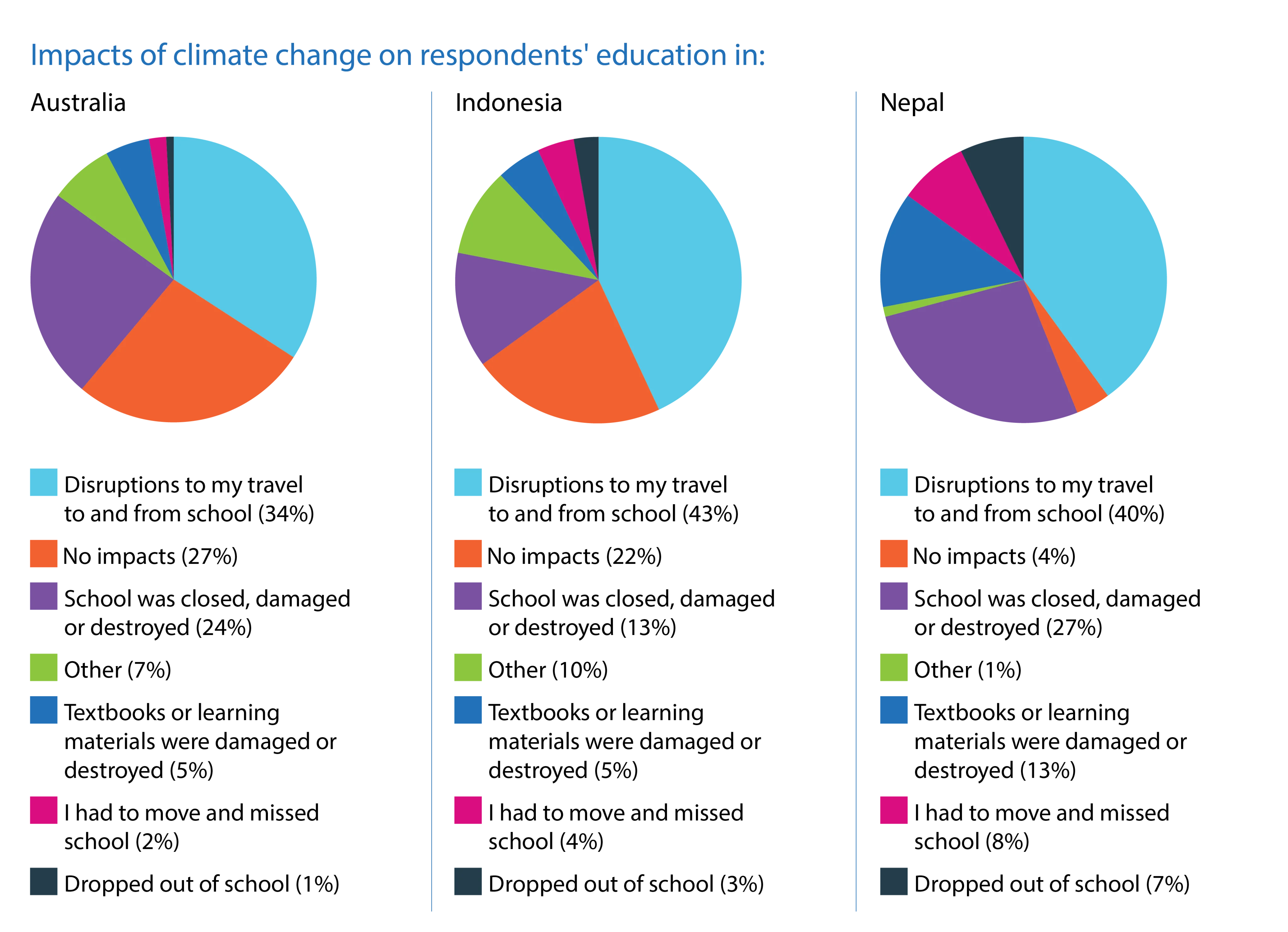

Girls are experiencing the impact of climate change on their education - from floods to fires, climate change is preventing girls from realising their right to an education.

Across all three countries, girls have experienced disruptions to their education because of climate- induced disasters. 98% of respondents said that they are very concerned or somewhat concerned about how climate change is affecting their school life, or how it will affect them in the future.1 The most common impact experienced was disruption to travel to and from school, as well as school closures.

Australia

In Australia, disasters exacerbated by climate change have impacted schools in recent years. The 2019 Queensland floods closed 38 schools, disrupting education for 17,900 students.2 The 2022 floods in NSW and Queensland lead to the temporary closure of almost 1,000 schools.3 The 2019-2020 bushfires affected approximately 1.65 million people in NSW alone, and approximately 30% were children and young people aged 0-24 years.4 The bushfires had a disproportionate impact on marginalised children and young people, such as those with a disability or First Nations young people. Almost one in ten children and young people impacted by the bushfires were First Nations young people. 3.3 percent of children and young people impacted had a disability.5

The 2022 floods in NSW and Queensland lead to the temporary closure of almost 1,000 schools.

The 2019/2020 Black Summer Bushfires loomed large in the memory of Australian girls who completed our survey. At the height of the Black Summer bushfires, almost 600 schools in NSW were closed, and 221 schools and early learning in northern Victoria.6disruption to their schooling because of these fires. For some, they were followed by floods the following year:

Climate change really impacted my education in 2019 with the fires, which my family was directly impacted by, putting stresses on my life and education. My school was shut down continually for most of December. I was not able to partake in any exams, which impacted my HSC years later on (combined with COVID, I had no examination prep). Floods followed the next year, closing access to school and my community, placing stress on my family and I again.

Indonesia

Indonesia’s location on the ‘Ring of Fire’ makes it one of the most disaster-prone countries in the world. Environmental degradation and the climate crisis exacerbate these natural hazards. Approximately one third of the national population lives in flood-prone areas.7 In 2021, approximately 100,000 children in Indonesia had their education disrupted by flash floods and landslides.8 At least 35,300 schools in Indonesia have been impacted by disasters from 2005 to 2019.9

In Indonesia, Tropical Cyclone Seroja impacted over half a million people in 2021, and wreaked havoc on the province of East Nusa Tenggara, displacing over 8,000 people. Alongside damage to wider community infrastructure, it also damaged schools, leading to school closures:

April 2021, the entire province of NTT (East Nusa Tenggara) was affected by a tropical cyclone that resulted in heavy rain for several days, accompanied by strong winds. This led to disruptions in education as roads, electricity, and buildings were damaged due to many fallen trees, floods, and damage to learning facilities.

Nepal

School affected by floods in Nepal - Image taken by Bardya.

School affected by floods in Nepal - Image taken by Bardya.

In Nepal, it is estimated that students are losing up to three months of education every year, due to climate disasters.10 During the 2017 floods, almost 2,000 schools were damaged or destroyed, and around 238,900 children missed school.11 In the worst hit areas, 90% of schools were destroyed.12

Respondents in Nepal reflected on how heavy rain and flooding is regularly causing school closures:

Due to heavy rainfall, the roof of my classroom was damaged. The water entered my class. There were not other spaces to shift our classes therefore school announced a holiday without any notice.

Girls' education is disrupted due to multiple, compounding extreme climate events.

Girls across all three countries reflected on an increase in compounding, extreme climate events. ‘Once in a lifetime’ weather events are experienced multiple times by girls today, and it is leading to more and more school closures. Children under 10 in 2020 will experience a nearly four-fold increase in extreme weather in their lifetime, compared to people aged 55.13

Respondents in Nepal reflected on the compounding impact of heavy rain, landslides and flood, alongside drought and heat waves:

Due to floods, the road to school is blocked. Even if you go to school, books and textbooks get wet when you are soaked in water...There is a different kind of weather than it used to be; sunny days in rainy season and no rainfall in rainy season or no water because of rise in temperature. As a result, schools are closed.

Australian respondents reflected on the compounding effects of heat waves and heavy rain as well:

In the past few years, the area where I studied was affected by major bush fires, and although my school was undamaged, it was closed for multiple days due to smoke. Heat waves and heavy rain have also made school attendance difficult on many days, heavy rains effecting buses, and heatwaves causing me to experience health issues that prevented me from attending school.

This is also disrupting girls’ travel to and from school. Feelings of being unsafe to and from school, and at school, was one of the most frequently identified cause for concerns by survey respondents because of climate change.14 Even when schools remain open, it is increasingly difficult for girls to get to school:

During significant floods, it's extremely challenging to get to school, even when using a motorcycle, due to the high water levels and long traffic jams.

Girls in lower income countries are hit first and worst. In Australia, First Nations young people are more heavily affected.

Even though the climate crisis is affecting girls everywhere, it is not affecting them equally. Girls in lower income countries are being hit first and worst, with less resources to respond to disasters and to invest in resilient infrastructure. These disparities are reflected in how climate change is impacting girls’ education in these three countries.

In this photo, Bardiya shows children travelling through flood water to get to school.

In this photo, Bardiya shows children travelling through flood water to get to school.

In her photo, Babita focused on a playground filled with water due to irregular monsoons.

In her photo, Babita focused on a playground filled with water due to irregular monsoons.

Although respondents from Australia and Indonesia spoke about impact on schools, it was students from Nepal that were worst impacted by floods, landslide and excessive heat.

Abdillah and Dhita, two youth activists from Indonesia, emphasised the significant impact of the flood that engulfed hundreds of homes in Ciamis Regency, occurring nine months ago. An unprecedented flood disaster that took two to three days to recede, indirectly triggering other disasters such as landslides. Although the disaster began with heavy rainfall and entered an increasingly damaged environment, the polluted condition of the river and the accumulation of waste also contributed to the higher intensity of the disasters.

Floods and landslides have occurred in the past, but the intensity was not as severe and frequent as it is now.

The severity of the flood disaster directly impacted the mobility of the community, particularly through blocked access roads and evacuation warnings that led people to be displaced. When experiencing flooding at this scale, both Dhita and Abdillah noted that school activities had to be temporarily halted. This situation also affects the health of the community and young people, as Abdillah explains:

Even at a young age, many of us are falling ill, and the effects come back to our access to education, which I believe is once again hampering our progress.

A still frame from Abdillah's video, showing the flooding in Ciamis Regency, Indonesia.

A still frame from Abdillah's video, showing the flooding in Ciamis Regency, Indonesia.

Uman in his photo story reflected how intensive rain following by flooding resulted in significant damage to the school’s infrastructure:

This damage includes crumbling walls, dirty chairs and desks from the floodwater, and most worrisome of all, a leaking and deteriorating roof.

In Australia, it is First Nations young people bearing the brunt of the climate crisis. First Nations people are disproportionately exposed to extreme weather events due to climate change.15 One in ten children affected by the Black Summer bushfires in NSW were First Nations children and young people, despite First Nations people comprising only 2.3% of the population in NSW and Victoria. Among the total First Nations communities in fire-affected areas, 36% are less than 15 years old.16

The impact of the climate crisis in Australia on girls’ education is also likely to differ significantly depending on where you live. For example, children living in Western Sydney experience more extreme heat compared to the rest of the city. During the 2019-2020 summer, Western Sydney recorded 37 days over 35 degrees, compared to only six in the city. The difference in temperatures across the city, from the coast to the west, can be as much as 10 degrees.17

A significant limitation of our survey was a lack of representation from First Nations young people, with only one respondent identifying as First Nations, and limited representations from other diverse young people.18

CASE STUDY

A tale of bushfires, floods and droughts – Australia, Nepal and Indonesia.

Georgia’s story

My name is Georgia, I’m from regional NSW, and in 2019 my town sat in the centre of two massive bushfires, the north and south. I remember my dad filled up the garbage bins with water, while we waited to hear if our school would make it. Many of the villages around my town were not so lucky, and for months after we drove through black forests of ash, a reminder of what had happened. I’m scared for this summer, and for every summer coming. If we don’t do something about climate change, this could be our new reality.

– Adapted from audio story

Samjhana’s story

20-year-old Samjhana is from Bardiya, the western region of Nepal. She lives in a Tharu community in Bardiya at risk of flooding from a nearby river.

Samjhana says, “Since my childhood, I have experienced major changes in my community due to climate change. My community has been transformed and understood a lot more about the different challenges that affected it and its members due to flood.”

She explains, “The situation I and my family faced due to the sudden rise in water level in the nearby river, heavy rainfall, and strong winds in 2014 will always remain in my memory.” she further adds, “I had not experienced such rainfall in my lifetime. I was just 11-year-old holding my mother tight so that I won’t be swept away with my house.”

"In 2014, I used to live a joint family with thirty-five members. We had four houses, three in the village and 1 away in the city. The houses are made of mud and bamboo, not cement. My family was a traditional one following ancient techniques to build houses that are not disaster resistant.

All three houses were easily swept away due to the overflow of water inside my house. It was nighttime. We were even not able to collect our important things like our school uniforms and books. When I woke up early morning, I could not find my house or my school. The whole community was drowned with loss of property but fortunately, there was no loss of life.

The incident still frightened me. Many times it makes me restless and worried about what else would have happened if the rain had not stopped, or if my family had not shifted us to the next place."

Samjhana’s family, like 80% of families in Nepal, are dependent on farming and cultivating varieties of crops in our field. "My family sells it and generates income that provides all our basic needs including fees for our school. Due to the flood in 2014, our store was also swept away where we used to store rice, wheat, crops, and vegetables."

"My mother and female members of my family cleaned the rice drenched in the mud and served the whole family wet rice for almost three days. We were starving for days and depended on the foods that were mixed with dirty water.

My elder sister’s leg was damaged by the water as she was working with my mother clearing the rice from mud. She could not get medical attention on time as the health post was half an hour away from my village.

In the daytime, we used to stay in a dry place near my house. But in the evening, we went to school to sleep. We did not have proper blankets and cushions to get proper sleep. I and my cousins was always hungry.

The school was closed for almost a month. Therefore, we had to stay with our parents who were busy shifting the remaining property to our house in the city. I did not have my uniform. My books and bags were also swept away.

I vividly remember ward officers visiting us in the school and providing some food, blankets, and other hygiene materials. This is how I was introduced to Plan International Nepal. The organisation provided relief and supported us with food, drinking water, and hygiene kits.

After a month, I was excited to go to school. The school provided us with new books, copies, and uniforms. I was worried about my studies and grades. But my school provided us with free extra classes and coaching before exams.

But for my parents, it took more than a year to build our houses again. The government supported Rs. 50,000 which was not enough. My parents had to take a loan to complete the house. For almost a year, we stayed under a tarpaulin.

Now I am participating in various orientations, training, and programs provided by the local government and Plan International Nepal regarding disaster responses. Therefore, I dream of becoming a police officer so that I can work as a rescue team during such disasters in my community."

Osin’s story

In her video, Osin shows the well which is commonly used by the people in their village. Extra effort is required to fetch water from a minimal number of wells that need to serve more than a hundred households.

"So, if we happen to arrive late and someone else arrives first, and there are more containers for collecting water, it means we have to wait until they finish fetching. And if, by any chance, they finish and the water runs out, it automatically means we won't have water in the morning when we need it for school or bathing."

Prolonged heat and drought have clearly caused difficulties for the community, including young women like Osin, in their daily activities. Especially in terms of its impact on education, Osin feels that her schedule is disrupted by the additional responsibilities she must undertake to meet her and her family's basic needs. Furthermore, this situation also affects her mood during educational activities at school, as she experienced during junior high and high school. "So if we don't get water, we go to school just washing our face, and I am impacted because it's hot during the day. So, I don't have the motivation to study, it's like I'm feeling weak, and I don't have the enthusiasm to learn. From the morning, when the teacher comes to teach, we are lazy, and eventually, we become unfocused in our studies."

Climate change is not just impacting girls’ ability to go to school, but also the quality of their education.

Girls commented on the impact of school closures on their learning and the quality of their education. Girls could see that they were not getting through the curriculum, and with textbooks and other school materials damaged, felt the frustrations about the lack of resources and how it impacted their studies. A decline in academic performance was one of the most frequent impacts of climate change on education cited by survey respondents across all three countries.

"Due to extreme heat, cold, and rain, schools are closed for longer periods of time due to which we cannot finish our curriculum on time. It is getting difficult to attend travel or attend classes due to extreme weather." - Nepali respondent.

Due to the flood, educational materials were damaged. It made it difficult to prepare for my exam.

Alif's image.

Alif's image.

[M]any schools have to be closed, especially those that have not yet reconstructed their infrastructure to raise their buildings higher. This extended closure of schools poses a significant setback for quality education. There is no support to ensure they can effectively continue their studies.

Beyond the classroom, respondents spoke about the impact of air pollution limiting their participation in sports and outdoor extracurricular activities, underlining the loss of important and nourishing parts of adolescence and schooling:

It really affects students, especially when we compare them to adults because their scope of movement is mostly indoors.

Della's image.

Della's image.

Water scarcity is a key issue for girls in the eastern region of Indonesia, and it’s impacting their education.

The climate crisis is not gender neutral. Women experience 260% more financial losses compared to 76% for men due to extreme heat, as women do the bulk of domestic chores, such as collecting water.19 Furthermore it is estimated that by 2040, one out of every four children will live in places with severe water shortages.20 This was highlighted as a key issue facing girls in the eastern region of Indonesia. It was a particularly gendered issue, with girls facing the increased burden of collecting water due to gender norms, impacting their ability to get to school on time, and to concentrate when they get there:

"In the last decade, climate change has resulted in droughts, which have hindered my ability to go to school on time. This is because of the inadequate supply of clean water (the river water has receded and is not clean, and there are long queues at the well to meet everyone's needs). As a result, my time to get to school is delayed, and it can affect the quality of my education." - Indonesian survey respondent

Wiwin, a youth activist from Indonesia reflected that the persistent drought in the area imposed additional responsibilities on young girls before heading to school, which included fetching clean water using jerrycans. To obtain this water, Wiwin, and alongside other children in Wiwin's village had to travel long and risky paths to other villages.

Carrying jerrycans through the river [to the other village] used to be done three to four times a week.

Wiwin's image.

Wiwin's image.

It was not uncommon for girls to miss school because they were asked to prioritise these chores, and for Wiwin, even when she did go to school, it was difficult to balance her schooling with these household demands:

I have difficulty managing my time. Because after returning home, I have to do household chores, fetch water again, and so on, and my study time is taken up by all these tasks.

Mogu's image.

Mogu's image.

Girls also reflected on the impact of water scarcity on girls' ability to manage their periods safely and with dignity at home and at school, and how this may impact their school attendance. Mogu, a youth activist from Indonesia, reflected on how her community coped with the water crisis following Cyclone Seroja, the impacts of which were exacerbated by the severe summer.

Mogu shows her concerns about water scarcity in her photo. She reflected that the water that she and other children collected was prioritised for the needs of the teachers' bathrooms at school. She expressed concern about how girls at school may not have access to sufficient water to meet their sanitation needs, especially during menstruation. Evidence shows that girls are less likely than boys to attend temporary school facilities after disasters, as girls and people who menstruate face additional barriers.21

Our crops are failing, and we can’t afford to attend school.

In her photo, Pude, a youth activist from Indonesia, shows her mother observing the condition of their garden after a landslide in 2021. Pude recounts that behind this photo, her mother had shed tears, recalling that the harvest that year had completely failed. In addition to damaging their family's garden, the landslide also blocked the access road.

When their livelihoods fail, the cost of their children's education may automatically be hindered... Because the results of livestock farming are also used for their children's education, so I really hope that everyone pays more attention to the water supply available in the village.

Pude's mother observing the condition of their garden after a landslide.

Pude's mother observing the condition of their garden after a landslide.

Pude's image #2.

Pude's image #2.

Pude's image #3.

Pude's image #3.

In their photos, Bandana and Manisha from Nepal show how crops have been damaged by flood and dry land.

Girls are worried about climate change. It’s impacting their mental health, and they’re worried about finding the jobs they want in the future.

The climate crisis is taking a huge toll on the mental health of girls, which affects their education. The IPCC concluded with high confidence that girls are at particularly high risk of mental health impacts from climate change.22 It’s not surprising that girls are increasingly worried about climate change – about the impact it’s having on their lives now, and what this will mean for their futures. They’re worried about having less power to make decisions about their futures – including the job they want and their academic progress.

In Australia 71% of respondents said that ‘less power to make decisions about my future’ was one of the top concerns they had about how climate change was impacting their education.

In all three countries, approximately 1 in 5 23 respondents in the survey said that ‘difficult finding the job I want in the future’ was one of the top concerns.

Girls feel that they have less choice about their futures because of climate change, and are angry that politicians aren’t listening to their concerns.

Girls are experiencing climate anxiety, but they’re also frustrated – with the lack of control over their futures, and that politicians aren’t acting on their concerns. They feel powerless:

In the end, the climate crisis makes them feel like they have no other option, and the only thing they can do is to carry on with their lives as usual, unlike people in big cities.

Australian YAS reflected that the options for young people to raise their concerns with decision makers are limited, with young women, girls and gender diverse young people often excluded from climate policy processes and decision-making spaces:

When you’re at school and when [climate change] is impacting your primary or secondary education, you don’t really have a connection to anyone with influence and you don’t feel like you can actually reach out to those adults in your life, or do anything about it.

Girls and young people want to learn more about climate change and green job skills – the current curriculum isn’t good enough.

Respondents across the three countries want to learn more about climate change, how to adapt to its impacts and how to influence climate decision making and policies. Education is key for learning about climate change - when asked what they want decision makers to do, girls also said they wanted to learn more about how to prepare for disasters.

Survey respondents from all countries have concerns about difficulty in finding the job they want in the future. In Nepal, girls particularly want to learn skills for green jobs, and feel that this is one of the top ways decision makers can address the impact of climate change on their education.

In Indonesia, girls want to see the curriculum move beyond theory, and teach practical ways to adapt to climate change. Almost 1 in 3 respondents in Indonesia wanted to learn more about how they can influence climate change policy and decision making.24

Iman's photovoice.

Iman's photovoice.

Youth activists from Indonesia reflected on this in their photos. Umam hopes that teachers can support awareness of climate change and how it is impacting their lives, and not just provide formal theoretical education. Abdillah hopes that an ‘environmentally based curriculum’ will be implemented.

Maria spoke about her work in engaging government agencies, and the need for decision makers to engage with young people, especially girls, more on climate policy. In collaboration with Plan International Indonesia, Maria conducted workshops with relevant government agencies to continue providing suggestions and recommendations, with the hope that environmental regulations, such as waste management, can be improved and enforced effectively to minimise climate-related issues:

Engaging with government agencies and advocating for better environmental regulations is a crucial step in addressing climate-related challenges in coastal areas.

Maria's image.

Maria's image.

In Australia and Indonesia, young women also spoke about the need for an intersectional focus on climate justice in the curriculum, and one which goes beyond climate science, into civic education, indicating their aspirations to be included and listened to when it comes to climate related policies in their countries.

For Australia, the importance of First Nations knowledge was seen as critical to this curriculum. They want a more intersectional curriculum, that looks at the unequal impacts of climate change, and the implications for government action and policies.

Investment case in girls’ education

- $15- $30 trillion: the cost to countries when girls worldwide don’t finish 12 years of education.

- 51.48 Gigatons: the potential reduction in emissions by 2050 through educating girls.25

- 25 per cent: the increase in girls’ future wages for each year of secondary education they complete.26

- 22 per cent: the return on investment in primary education in low-income countries.27

- 12 times more cost effective to invest in climate resilient school infrastructure than disaster relief assistance.28

Girls' activism gives them hope for their future – but the responsibility to address the climate crisis lies with wealthy countries and big polluters.

Despite the impact of climate change on their education, girls are active agents of change, and we saw this overwhelming in the work of the young women involved in this project and the girls who shared their stories via our survey. Their climate activism, and the activism of girls around the world, gave them hope for their future, and made them believe that change was possible.

All these concerns about climate change led me to join communities and take part in actions to address this issue. I became passionate about understanding and combatting climate change, shifting from being concerned about global warming to becoming a global educator. I realised that I needed to care for my environment, and I felt responsible for sharing my knowledge about it. Instead of panicking, I saw it as an opportunity to make a positive change. I distinctly remember being a Year 9 student at an all-girls school, having recently moved to Australia, I felt uneasy about socialising and participating in something as big as a strike. Through conversation and sharing of passions for climate and gender justice I gathered up the courage (and some friends) and made the decision to participate in the school strikes for the climate movement. This movement was inspired by Greta Thunberg, who had sparked conversation amongst my classmates, teachers, friends and family. It was the talk of the year to me at least, and millions of people were coming together to make impactful change so of course I had to speak out too.

Girls and young women are leading the call for climate justice globally – but it is not their responsibility to fix the problem. The responsibility for climate action doesn’t sit with them alone, and the young women involved in this project were adamant about the need for government to take greater action, listen to their solutions, and implement real change in response to the climate crisis.

Loss and Damage

Loss and damage refers to the destructive impacts of climate change that cannot be avoided and go beyond what people and communities can adapt to.

It can also refer to a community’s lack of access to funds or resources in a community to deal with loss and damage.

Loss refers to consequences that are irreparable, such as loss of life, biodiversity, cultural heritage, and Indigenous knowledge. Damage speaks to the consequences that can either be restored or repaired – for example, houses, schools, hospitals, roads, and bridges.

However, some loss and damage can’t be quantified in economic terms – as this report shows. For girls, it comes in the form of lost school days, lost rites of passage, loss of Indigenous knowledge, and loss of hope for the future.29

Wealthy countries, from Germany to New Zealand, who have contributed most to climate change are stepping up to support low-income countries devastated by its impacts. These countries are making contributions to loss and damage finance, Australia must join them and help build this momentum towards climate justice.

Sign the petition urging Environment Minister Chris Bowen to invest in a global loss and damage fund.

Our Vision for a Better Future - Recommendations

Disrupting power, and girls leading the way in a climate changed world.

1. Establish a National Council of Young Women on Climate.

Loss and Damage.

2. The Australian Government to make a financial commitment to the Loss and Damage Fund at COP28.

3. Child rights recognised as a guiding principle in loss and damage funding allocation.

4. Disruption to education recognised as a form of non-economic loss and damage in the UNFCCC Loss and Damage Fund.

5. Funding from the loss and damage fund should be used to help girls realise their right to an education during the climate crisis.

Prioritising girls’ education during the climate crisis and enhanced disaster preparedness.

6. Allocate resources and develop policies that ensure girls' education is maintained and protected during climate-related disruptions.

Connecting girls for collective power.

7. Development of an app –based and module- based toolkit for climate change action, risk assessment, mitigation and activism.

8. Technology and digitalisation used for education continuity.

9. Local governments to prioritise the strengthening of girls' and young women's networks and groups, giving them a platform to advocate for climate action and gender equality.

View and download a copy of the For Our Futures report.