News and Stories - Advocacy - 23 October 2018

Saúl Zavarce: Champion of Change

Saúl Zavarce is Venezuelan-born, a passionate advocate for gender equality and a great dancer. He is also Plan International Australia’s Campaigns and Youth Officer and recently delivered this speech to a 600-strong audience at the annual breakfast event organised by the International Day of the Girl Adelaide Committee.

Buenos dias, good morning, my name is Saúl Alexander Zavarce Corredor.

Before I begin, I would also like to acknowledge the Kaurna people, the traditional owners of the land we meet upon today, and to pay my respects to elders, past, present and emerging.

I also acknowledge that we meet on stolen land, that sovereignty was never ceded.

I would also like to acknowledge the many women in my life, and in the lives of the men in this room today, for the labour they have put in to teach myself and us, to be that little bit better.

Today I have a privilege to be talking to you all on how men and boys can be better allies in the mission for gender justice; I am here today because women taught me how to be.

A little bit like this.

I am Plan International Australia’s Campaigns & Youth Officer. My role currently involves the management of the Youth Activist Series, where I organise groups of young women, developing their professional skills and putting them into positions of influence to speak truth to power – to advocate.

I am passionate about young people, I believe they have all the answers to their problems; they just need someone to ask the right questions.

I started my career in in high schools, facilitating workshops with young men aged 14-16, deconstructing and reimagining masculinity and now get to support this same work at Plan International Australia.

Today, we have been discussing the role of men and boys in gender justice, in the mission to unlock the power of girls, women, and other genders.

Men and boys play a crucial role in advocating to other men and boys to end violence against women.

I was born in Caracas Venezuela.

Venezuela is a country on a margin, it is in South America, but it has a culture more like that of the Caribbean where its coast lies.

It is the middle point between sub identities, not quite South American, not quite Caribbean in nature, something in between.

We moved to Australia when I was two years old, and while I grew up in working class multicultural schools, my home life was and still is, well and truly Venezuelan territory.

I would wake up to shouting in Spanish, leave the house and study in English, and come home to eat arepas, be forced to play baseball by dad, and listen to salsa on the weekends.

In every sense, I have grown up on a margin, in a middle point between sub identities – Venezuelan or Australian? I am both and more.

The archetypical masculinity that Latin Americans, and in particular Venezuelans perform is very different to the Anglo-Saxon masculinity that we are accustomed to here.

Venezuelan men stereotypically are very passionate. We are extravagant and romantic, controlling, hypersexual, and above all else good dancers.

A man who cannot dance in Venezuela is only half a man – or so the saying goes.

In Australia, the most valued performance of masculinity is a mild mannered, restrained, tall handsome man.

He’s intelligent, witty, does not cry, plays footy, always has the answer and is above all else rational.

He might be able to dance, but also if he doesn’t, it’s not that big a deal, after all dancing is “kind of gay” here.

I grew up learning English and Spanish, white and Latinx masculinities at the same time.

It was a big task for a 2 year old, so big that I didn’t actually speak either language until I was four years old.

I grew up in a house where dancing salsa was encouraged and a school where dancing was “gay.”

I refused to learn to dance until I was in my early twenties – I was denying myself one of my life’s greatest pleasures, part of my heritage, in order to fit in.

Because of this, I found it very difficult to make friends as a child. I wasn’t able to speak the language, but also, I was growing up with very different customs to the children I would meet at school.

Add to this the extra element that I also have Tourettes Syndrome; I was bullied very heavily from primary school right through high school.

My nicknames in primary school were Ah-Saul (asshole) and Dirt, because I was marginally darker than my classmates were.

My entire life, I have lived with a sense of alienation, a sense of being an outcast/outsider, and thus been self-sufficient and independent.

When I got into high school I turned from quiet, reserved and bullied boy, into rebellious punk without a mission or cause.

I had a really nasty habit of rejecting everything with radical anger.

I was a wounded child, and the masculinity I performed was wounded. An exaggeration.

I began to abuse its power. I found my people, or so I thought, when I picked up the bass guitar and was surprised to find that I was finally good at something.

Music was a gateway to friendship for me with other rebellious teens.

My masculinity was also a rejection of popular masculinity, I wore lipstick, I wore eyeliner, I wore crop tops and gigantic earrings, and I loved and still love to gender-bend, because rebellion is where I feel safe.

I failed high school terribly. Teachers had no idea how to reach me because I had/have such an issue with authority. It didn’t matter, “I was going to be a rock star anyway,” I would say.

And I was! I played in bands from 17 to 23, touring all around Australia, being flown to the USA to record, we were signed to a record label, I ticked all the boxes for the title.

I was also miserable.

I was always in bands with racists, my name was never Saúl, it was Taco, or Blackie, again because I am marginally darker than they were.

I needed to get out because the life of a musician was not what I wanted for me.

At 21 almost 22, I finally got into university for journalism, on a whim I chose Gender, Sex, and Knowledge.

I was 21 the first time I heard “extreme reliance on masculinity to be respected is toxic to men”.

21.

It blew my mind.

Of course it is.

This was a class that gave me the opportunity to think critically, “why is my masculinity based upon rebellion, what power do I seek from this, why is anger so useful for me, why is anger so safe for me?

Why do I want to dance but refuse to out of shame? What is bringing me this shame?”

This was me when I started university.

What I learnt is that the toxic effects of male privilege are a lot like alcohol. Alcohol is literally a poison that we ingest in small amounts for its pleasurable effects, but that in excess can grow to become a dominant force in our life, defining and framing almost all our interactions with the outside world and ourselves.

Toxic masculinity likewise is something that all men have been taught to play into from time to time, to get the privileges that come from it.

Addictions are challenged only when they hamper our ability to function, when they are used to self-medicate from trauma or fill the gaps that would normally be filled with strong valuable relationships.

To quote bell hooks “the first act of violence that patriarchy demands of males is not violence toward women. Instead, patriarchy demands of all males that they engage in acts of psychic self-mutilation, that they kill off the emotional parts of themselves.

“If an individual is not successful in emotionally crippling himself, he can count on patriarchal men to enact rituals of power that will assault his self-esteem.

“Patriarchy demands of men that they become and remain emotional cripples.”

Male reliance upon masculinity quickly leads us into a space in which we must prove to ourselves and others our manhood.

We must “perform” in order to refute any possibility of being called a woman, and this begins the cycle to keep our manhood, the very force of their oppression.

The further we lean into this insecurity of being viewed as women, the more we engage in toxic behaviour.

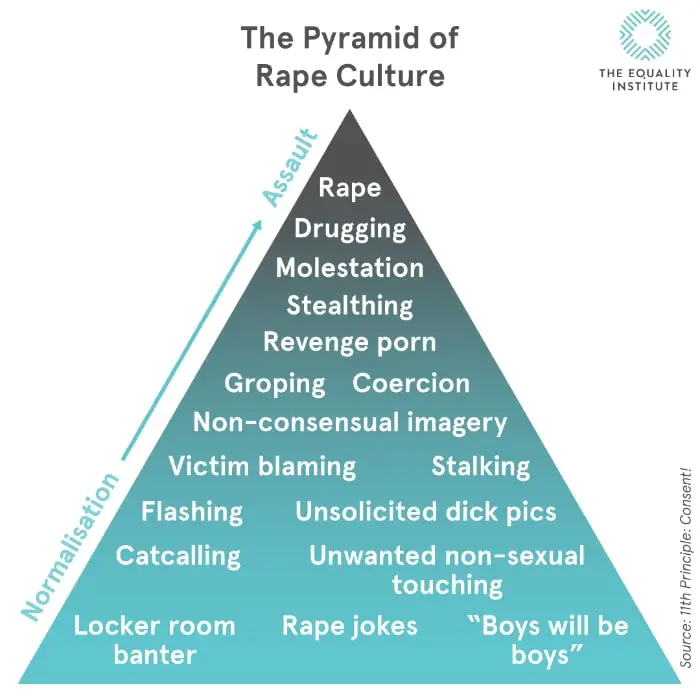

Toxic behaviour starts small. Little jokes here and there, boy banter and “locker room talk”.

These seemingly “harmless acts” form the basis for much more toxic and alarming behaviour however, as the above image shows, this is the foundation for acts far worse.

For many, masculinity is the one thing that the patriarchy won’t take from them.

It will take away their ability to articulate feelings, to be introspective, to properly love, it will emotionally cripple us, but it won’t take away our manhood, and that makes it all the more dangerous to rely on just that to be taken a human being worthy of respect and dignity.

21 is too late for young men to be thinking critically about the societal forces and stereotypes that people project onto them that they aspire to replicate.

Young men need to be given space to do the same as young women have thankfully recently begun to do: to question gender roles.

Imagine if at 14 I had questioned: Why dancing is “for gays” if you’re white, but also necessary if you are Latinx?

Plan International’s Champions of Change program does this precise work with young men.

As a youth worker who has delivered these very lessons and facilitated these discussions with young men, they come out with a new sense of expanse.

That they are imperceptibly huge and beautiful creatures with boundaries that are not defined by the narrow definitions of masculinity that society has painted for them.

Champions of Change was born out of Plan International’s desire to see a world where all girls can live free from fear and violence.

It was an expressed acknowledgement that women and girls can’t end gender based violence on their own; that it can only be done if we engage men and boys in examining what fuels discriminatory attitudes and anger towards women and girls.

Champions of Change works by taking boys and girls through an interwoven journey of critical thinking.

All genders involved will learn 90% of the same materials; however, young men and women are separated in the first workshops to receive tailored information.

It seems simple – gather a group of young men with a leader they connect with. Meet regularly to really discuss what it means to be a man.

Through the workshops, boys go through a process of reflection and questioning, interrogating and ultimately deconstructing masculinity. Giving them the opportunity to rebuild their concept of masculinity with the pieces and values they want, leaving out those they feel harm them or are not useful.

It asks: who are the men in our life that have taught us how to be men? What do I love about them? What do I wish to not learn from them?

Within the girls’ groups they instead look at how they are represented in media, they discuss self-esteem, they discuss bodies, “ideal femininity” and the pressures that aspiring to such an ideal has on them.

They go on to discuss gender at home, who cooks, who cleans, who gets to go to school?

Then, young men and young women meet and work together.

They discuss the challenges and pressures that the other has.

They listen to each other.

This is a process of building empathy between these gender groups, to remove ignorance of the other’s experience, and to see each other as fundamentally human.

Most crucial of all, Champions of Change is an exercise in movement building, Plan International is trying to educate young people to see each other as worthy of each other’s collective effort.

To advocate on behalf of the other, to bring us together.

This video can show you directly from Ugandan participants, what Champions of Change looks like.

The first Champions of Change programs were piloted in Latin America.

This region as I have alluded to really needs this kind of work because of its traditional patriarchal understandings of the roles men and women are supposed to play and because of its high rates of gender based violence – a direct result of how controlling our understanding of manhood is.

The full Champions of Change program is now being expanded to other regions around the world and elements of it have been adapted throughout Plan International programming including the Safer Cities and Free to Be mapping project that those of you who attended the breakfast last year will have heard about from my colleague Deb Elkington.

This is work that is fundamental not just in developing contexts, but also in developed contexts.

After all, I was 21 when I first was asked to question “what is masculinity?”

If I as a Venezuelan Australian was in a place where my masculinity was one of the only tools I thought I had to assert myself, imagine the consequences when we have a group of physically, socially, economically, and violently oppressed men, whose only tool left is a toxic overcompensation of their masculinity?

It took me six years of higher-level education and a debt of over $50k to even begin to unlearn the conditioning I had received as a young man, and this shouldn’t be the case.

Plan International by delivering this education is in the process laying the foundations for the next generation’s increasingly revolutionary approach to gender.

We are short-circuiting the system so that no child must be twenty-one before they even begin to question the forces that shape them.

It is up to us as individuals, especially men, to embark on the journey of creating a true movement of introspective and emotionally intelligent men.

To create a movement for righteous self-reflection that acknowledges the structural power we wield through toxic means.

You can play a role in ending violence against women by fostering and encouraging this journey within the men in your lives, getting us to ask:

“why DO WE believe that we can’t wear those shoes?”

“why DO WE shame boys for dancing?”.

You can help us get this message out to young people and to start these conversations and lessons by donating to Plan International’s work for girls and boys.

Radical change like the one that is needed to shift the cultural understanding of manhood will never come from the top down, it will be a movement by definition.

If we do this together, we won’t just be supporting girls and boys and all children to achieve their dreams. We’ll be supporting them to reimagine their world and their roles in it, together. Imagine what that world could look like.

Gracias.