News and Stories - Health - 14 December 2018

Her First 1000 Days

A new life is something to be celebrated and nurtured. A child’s first 1000 days, spanning from the moment of conception up until their second birthday, will influence their health, growth and learning potential for the rest of their lives. We want every newborn baby to have the best possible start in life, but around the world, particularly when extreme gender inequality exists, some babies are disadvantaged and discriminated against, because of one characteristic.

They were born a girl.

Those first 1000 days of life are a critical period of rapid learning and development and a window of opportunity for parents to lay the foundations for their child’s future health and wellbeing. This is the period that sets a child’s trajectory for the future. But it can also set a path of entrenched inequality that can hold children, and girls in particular, back from achieving their potential.

Poverty and food shortages. Conflict and crises. Families lacking the essential information, tools and resources they need to help their babies thrive. All these things can have a significantly negative effect on a baby’s health and development during pregnancy and into the future. When gender inequality exists, the gap between girls and boys starts here. The vast majority of parents want their children to be happy and healthy. But when gender inequality exists, so too does a perpetuating cycle. It starts with the wellbeing of expectant mothers and can run through to when their daughters become mothers themselves.

A preference for sons in some contexts sees boys favoured, prioritised and valued over girls and when this is the norm, a baby girl is not something to be celebrated. She will never be the breadwinner and she cannot carry on the family name. She will be sold off once she is old enough to marry and that is the only way her family will profit from her existence.

While this belief is harmful in itself, it is exacerbated in situations of poverty and crisis. Son preference mainly appears in contexts where families have limited resources and, based on cultural gender norms, they choose to invest more of the little they have into the care and education of their sons.

During early childhood, this can mean a baby girl is prioritised last, underfed and undernourished, neglected and not provided with adequate health care if she becomes unwell. In some countries, extreme actions, such as sex selective abortions and even infanticide (the killing of a baby after birth) have been introduced to prevent families from having to raise a daughter at all.

If a girl survives early childhood, the inequality doesn’t end there. Her low status will continue as she grows older – girls have less access to education (there are currently 130 million girls not in school) and very little say in their future. If a girl isn’t in school, she is more likely to be forced into child or early marriage and to fall pregnant early. She will lack the vital health and nutritional knowledge needed to look after herself and her child, and if she is undernourished or in poor health, the health and development of her baby – no matter their gender – will also be hindered.

The impacts of gender inequality are far reaching for men and boys as well as women and girls. The cycle of inequality will perpetuate, on and on, unless we do something to help families end it.

We are working to put a stop to this cycle, so that all children can survive and thrive. We are working in partnership with local communities to tackle the root causes, to give every child the healthiest, happiest first 1000 days and beyond.

And you can help us.

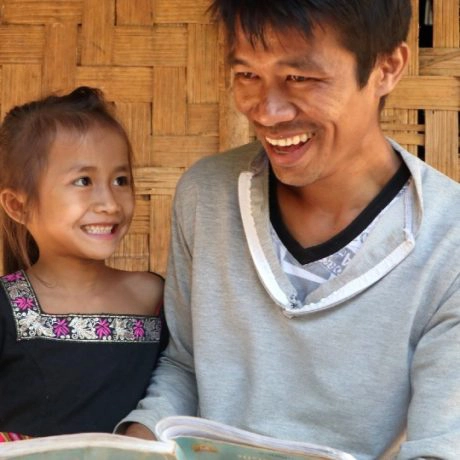

We’re collaborating with local partners around the globe, supporting them to start parenting groups in their communities. In this space, we are breaking down gender norms by engaging with both mothers and fathers, supporting fathers to be emotionally and practically engaged in their child’s upbringing and ensuring mothers have access to the tools and education they need to end the cycle that disadvantages girls from birth.

Through these parenting groups, women receive breastfeeding support and parents learn about the importance of nutrition and food hygiene. They receive information on milestones so they can track their child’s progress and they learn how to engage in stimulating care and play for their child’s brain development.

Sushma is a mother of two young daughters. She lives in Rajasthan, India, a state where four out of ten children are underweight. “Every mother wants her children to be healthy, happy and active. She wants to see them playing, learning and growing. But this was a distant dream for me,” says Sushma. “I was not aware of what and how to feed my children, so they grew weak, got tired easily and were unable to focus.”

We have been working in Sushma’s village, delivering nutritional information and water, sanitation and hygiene training to improve the health and development of children during their early childhood. Since taking part in training, Sushma has taken her daughters to a malnutrition treatment centre and the information she was given has been invaluable. “I followed all the advice and since then, both my daughters have blossomed” she says. “They are now very active! I am happy, as after all, healthy children are every mother’s wish.”

Every child deserves to have the best possible start in life, regardless of their gender. Donate to our work today and help us support children during their first 1000 days.