Holding On To Education In Somaliland

“Sometimes we have breakfast and sometimes we don't have it. I feel hungry when I have classes. When I'm hungry I can't study well.”

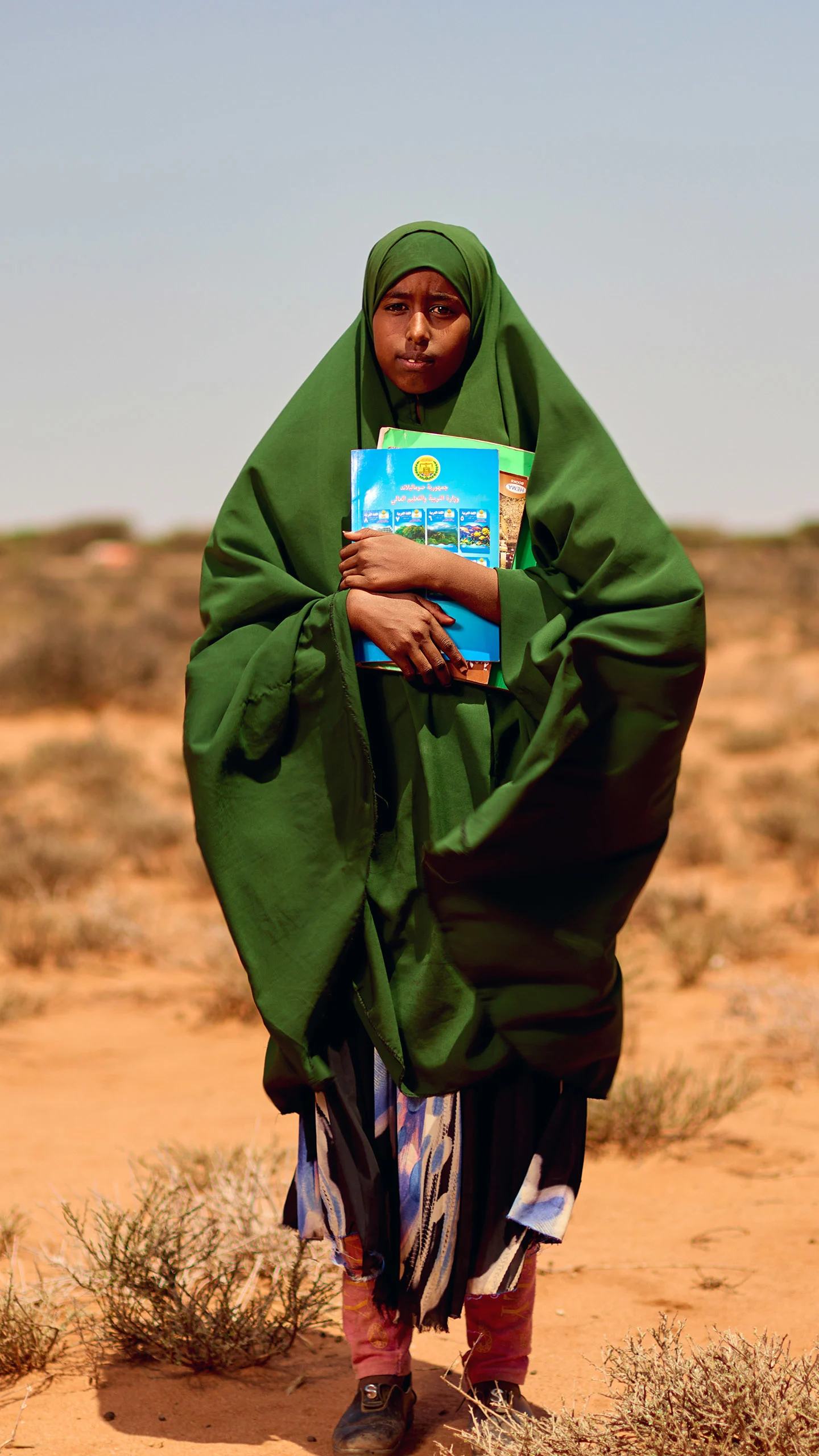

12-year-old ZamZam, from the Togdheer region of Somaliland, is one of the lucky ones. She is still enrolled in school. But the severe drought in Somalia, which has bought the country to the brink of famine, makes holding on to her education a constant challenge. Like many of her classmates and friends, ZamZam is having to split her daily time between attending classes and fetching water for households and animals from ever decreasing and distant water sources. Women and girls are mainly responsible for water collection as part of their household duties.

"Since the drought started, we often miss school because of other priorities at home such as taking care of animals and fetching water for the family. The water collection points are now quite distant. If we leave at 8:30am to collect water, we don’t get back home until around noon, and that’s how we miss school." explains 18-year-old Hibbaq.

More than two decades of conflict have crippled Somalia’s education system, and the drought has compounded an already dire situation for girls. Even before the rains failed, more than 70% of school-aged children were out of school. Due to cultural practices and gender beliefs, girls were already more likely to be taken out of school, putting them at greater risk of sexual violence, child labour and early marriage.

Of the 2.4 million school-aged children affected by the drought in Somalia, 1.7 million are now out of school.

Like ZamZam, Hibbaq is still in school, but the impacts of the drought on her education are evident.

"Our school has one classroom that has all children from grades 4 to 8. All the children sit together facing one blackboard. The class is divided into three parts and one teacher gives lessons to all children but at a different fixed time. When the teacher gives us homework, we wait until the morning and do it at school because we don’t have any light at home. The school toilets don’t have locks and we don’t like to use them." says Hibbaq.

In a vicious cycle, schools are closing due to low numbers, forcing those still enrolled to travel further to learn. These arduous journeys, usually while hungry and without any water to drink, is causing more to drop out.

"We walk long distances to get to school, and we are afraid that we might meet a person that may treat us badly. We also fetch water as a group to reduce the risks of being attacked by someone, but when my neighbours have water I have to go alone because I have no choice."

Help girls hold on to their education.

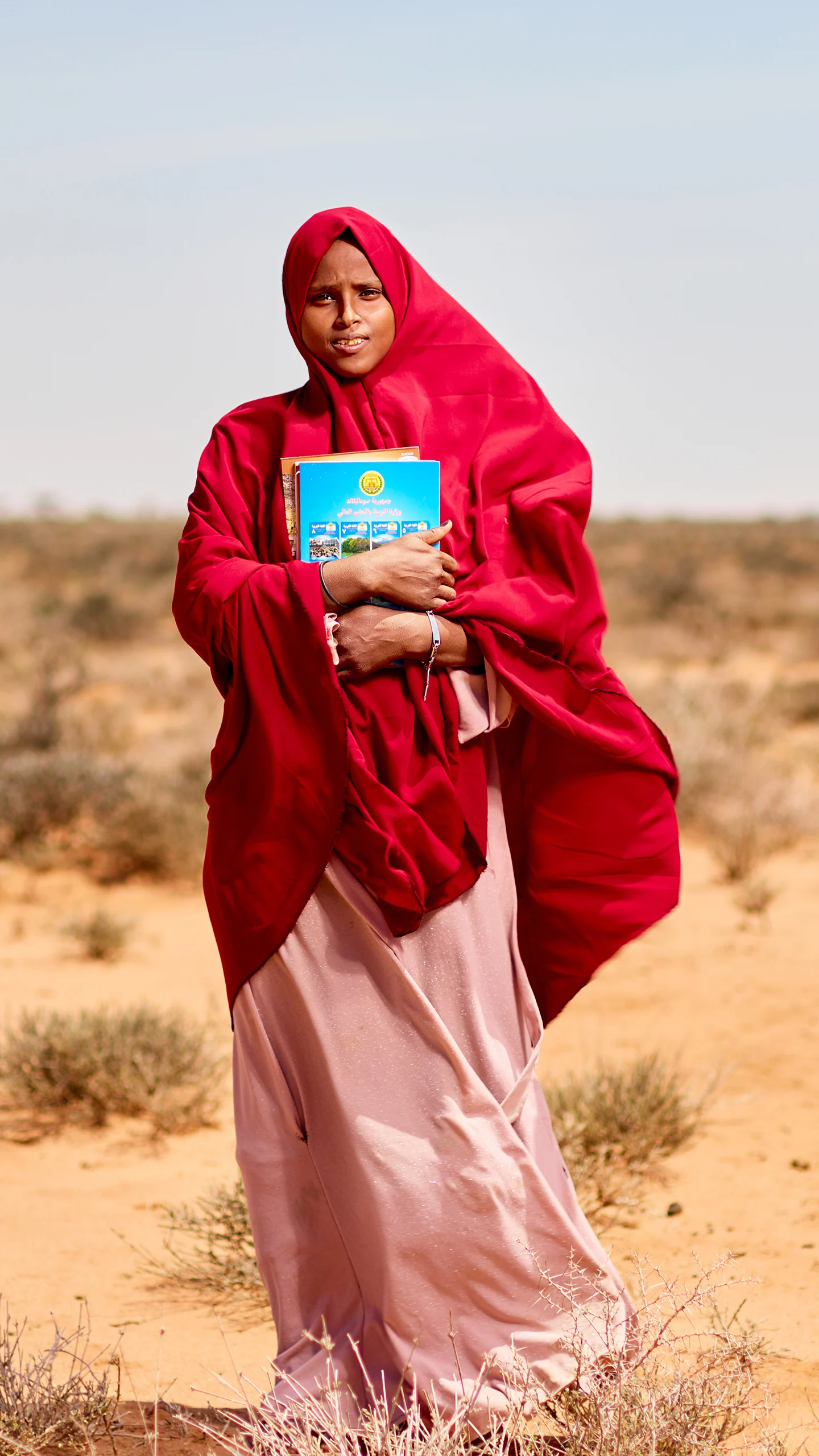

12-year-old Juweriya, along with her mother and grandmother, moved to be closer to water and essential services after all their livestock died, which for pastoralists families means loss of livelihood and income. There is little food to eat and the family are badly undernourished.

"We eat twice a day. Food has run out, and the fields where food used to be brought from have dried out. So we only cook two times a day. Sometimes I have breakfast and sometimes I don't get it. I get sick sometimes. When I have breakfast, I am okay, but when I don’t have breakfast, I get sick."

But she is determined to continue her education. "Most mornings I wake up at 5am as I have to be at school by 7am. If at 7am we are not there, we will be in trouble. I get up early, I pray, put tea on the fire, fetch water and then go to school. I come every day."

Donate now to help girls' hold on to their education. Your gift can help fund feeding programs in schools, provide families with vital basics like food, medicine and school supplies, set up emergency classrooms and learning programs, and provide parenting skills workshops to improve family dynamics and explain the benefits of girls' education.