Plan international Australia works with partners to harness the power of International Women’s Day to drive action and raise vital funds to support girls and women around the world in some of the most challenging environments to ensure every child, no matter where they are from, has the right to safety and equality. Find out how you can get involved!

International Women’s Day 2024

How you can partner

with us on March 8th

Fostina, 27, Zambia.

Fostina, 27, Zambia.

On Friday 8th March 2024 the world will celebrate International Women’s Day. A day to unite and challenge stereotypes of women, broaden perceptions of what is possible and celebrate women’s achievements.

Plan international Australia will work with you to harness the power of International Women’s Day to drive action and raise vital funds to support girls and women around the world in some of the most challenging environments to ensure every child, no matter where they are from, has the right to safety and equality.

Why We Exist

Plan International is a global development and humanitarian organisation, with a special focus on girls and children. We work with over 55,000 communities, across 85 countries, advancing children’s rights and equality for girls through education, protection, empowerment and emergency support.

We believe in the power and potential of every child but know this is often suppressed by poverty, violence, exclusion and discrimination.

And it is girls who are most affected.

For over 85 years, we have supported children’s rights from birth until they reach adulthood. We enable children to prepare for and respond to crises and adversity and drive changes in practice and policy at local, national and global levels using our reach, experience and knowledge.

We won’t stop until we are all equal.

But we cannot do this alone…

Solitha, 27, Tanzania.

Solitha, 27, Tanzania.

JOIN THE MOVEMENT

We are asking brands and businesses across Australia, to come together on International Women’s Day to #CountHerIn by raising vital funds to accelerate progress for the next generation of women.

This could be done by:

- Creating a bespoke product to sell around IWD

- Donating a percentage of product sales for the week or month of IWD

- Making a one-off donation

- Engaging employees to fundraise

We have a dedicated team ready to support you and your team to make it as simple as possible to join the campaign. Our IWD toolkit comes with prepared campaign assets, imagery and content to use across your own channels to connect with your customers and clients through a shared cause.

Image captions

-

Image 1

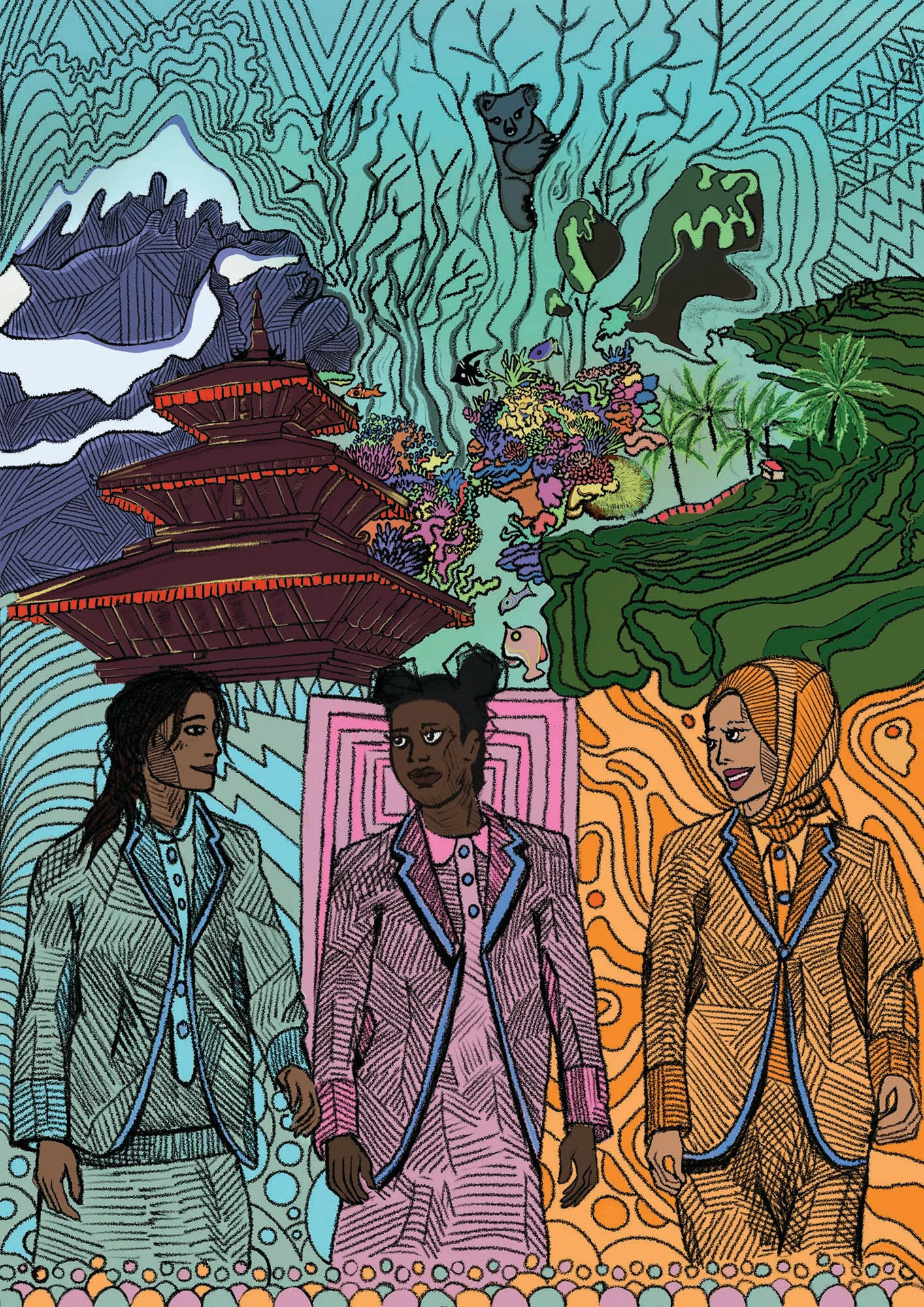

Image 1Evita, 13, Solomon Islands.

Evita, 13, Solomon Islands.

Evita, 13, Solomon Islands.

Eunice, 18, Mozambique.

Eunice, 18, Mozambique.

Barwaaqe, 19, Somalia.

Barwaaqe, 19, Somalia.

Salimata, 12, Mali.

Salimata, 12, Mali.

12 million girls are forced to marry as children every year – every 2 seconds

Every 10 minutes, one adolescent girl dies as a result of violence

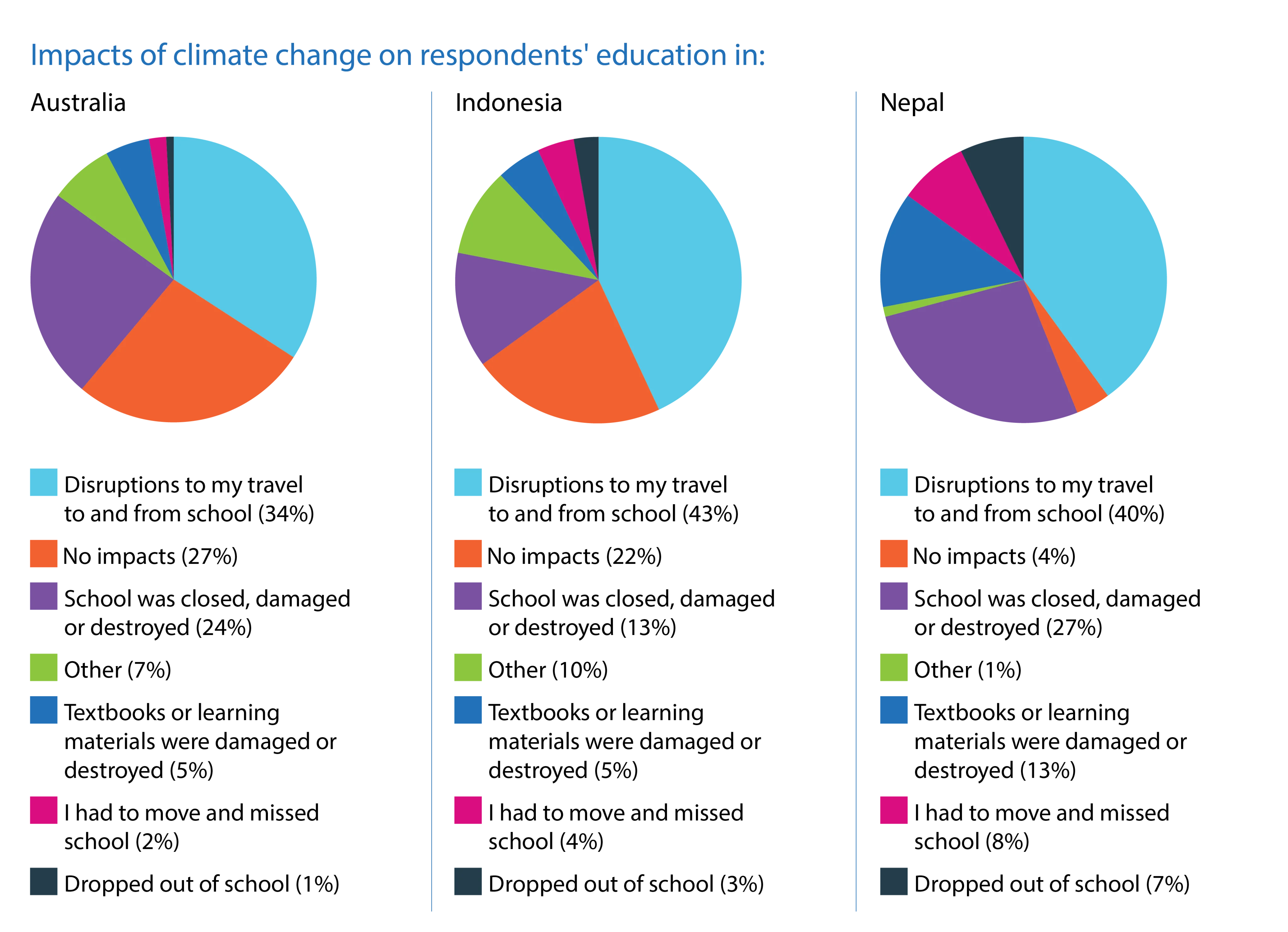

12.5 million girls could be prevented from completing their education due to climate change by 2025.

We can’t wait for opportunities;

we must actively seek them,

and when they aren’t readily

available, let’s create them.

Let’s empower ourselves and

each other, and build a world

where gender doesn’t limit

our potential.

It’s a journey worth embarking

on, and together, we can make

it happen.”

Akriti, 21 – Nepal

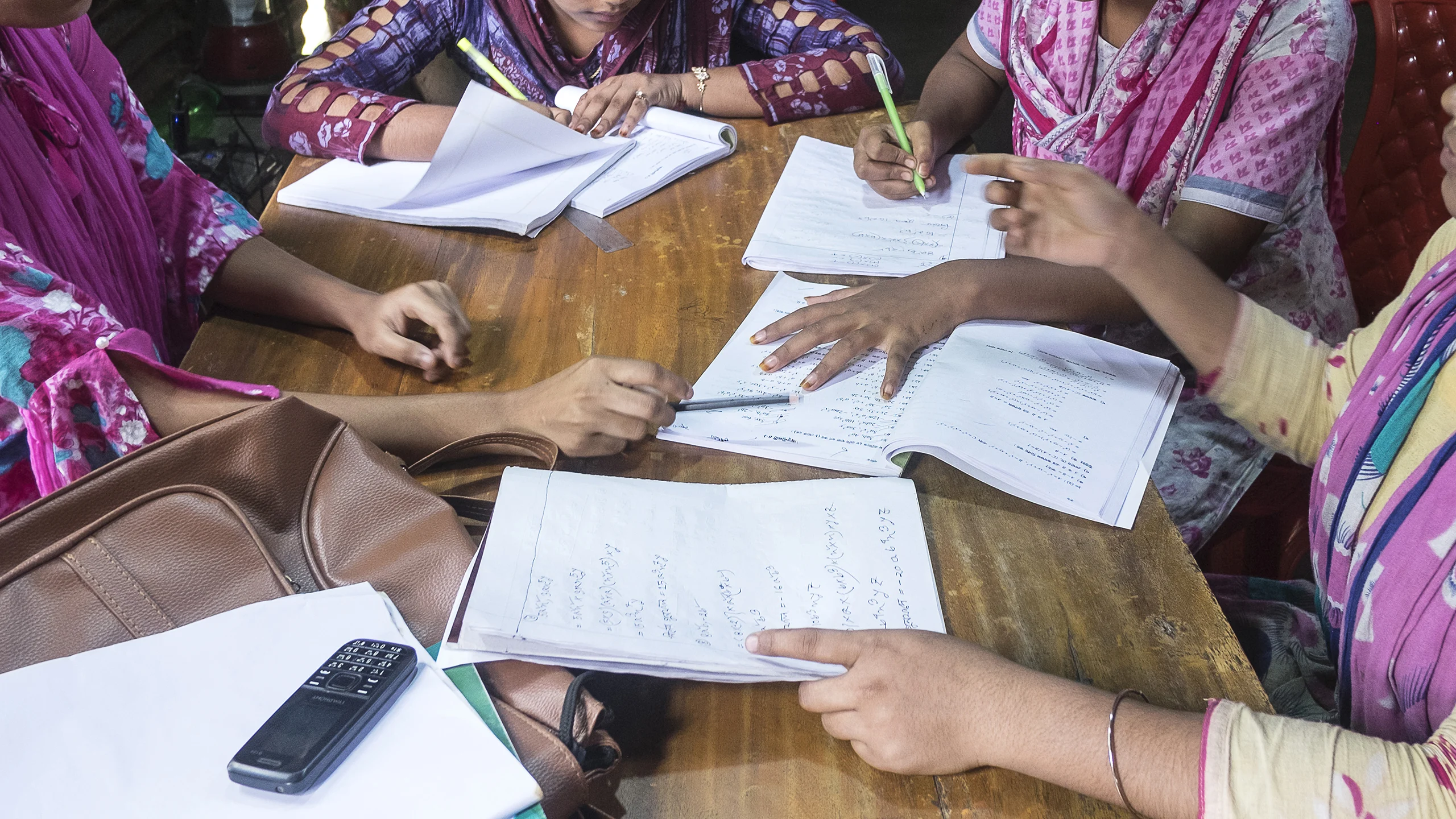

Your contribution will provide life changing support for girl’s across the world by ensuring that even in some of the most challenging conditions, they will have access to safety, education and dignity.

$7,000

could boost financial independence for women by providing 30 young women with a 3-month training course in skills like hairdressing, sewing or computer repairs and assistance to start their own business.

$10,000

could support girls continue their education during emergencies.

$15,000

could help girls manage their periods with dignity and continue to attend school by providing materials to build 4 girl-friendly bathroom blocks in schools.

Papinelle raised $2,500 through a bespoke collection dedicated

to IWD.

The Body Shop donated $1 from every transaction to Plan International over the weekend of IWD.

They then went on to donate $5 from every purchase of The Body Shop’s Shea Nourishing Body Lotion.

INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S DAY 2024.

Eunice, 18, Mozambique.

Eunice, 18, Mozambique.

WILL YOU JOIN THE MOVEMENT AND #CountHerIn?

If you want to get involved, get in touch via email: